Divine Stability

I posted this on the EZ Board months and months ago, but I'll resuscitate it here because the ashtanga vinyasa practice is woven with stories, and who doesn't love a good story?

Vishwamitra

Vishwamitra is one of Hinduism’s most venerated rishis. He was a kshatriya warrior-king by birth, but became a rishi through thousands of years of hard penance. He is also known for discovering the Gayatri mantra.

In the Ramayana, Vishwamitra trains Rama and Lakshmana in the use of the devastras, or celestial weaponry, and guides them to kill powerful demons.

Although “Vishwamitra” means “friend of the universe,” one of the rishi’s chief faults was his short temper. He was quick to anger and often cursed hapless victims, thereby depleting the yogic powers he’d obtained through much tapas.

As per a reader's edit, "it should be noted that Visvamitra became a brahmin-rshi, not just a rshi. A significant difference is there. As for his name, it can mean "friend (mitra) of the universe" or "enemy (amitra) of the universe."

Vasishta

Vasishta was chief of the seven venerated rishis and the preceptor of the Ishvahu clan, also referred to as the Surya dynasty. He was thus the guru of Rama and Rama’s father Dasaratha. Vasishta is Brahma’s manasaputra, or “wish-born son.”

Pattabhi Jois highly recommends reading the Yogavasishta, an Advaita Vedanta text in the form of a dialogue between Vasishta and his student Rama.

Kasyapa

According to the Mahabharata, the Ramayana and the Puranas, Kasyapa was the son of Marichi, the son of Brahma. Kasyapa, which means “tortoise,” was one of the seven great rishis. He had numerous and diverse offspring, including demons, nagas, reptiles, birds, and all kinds of living things. He was thus the father of all, and as such is sometimes called Prajapati.

According to the legendary history of the Chan and Zen schools of Buddhism, a monk named Kasyapa received dharma transmission directly from the Buddha at the famous flower sermon. The Buddha silently held a flower before his students and only Kasyapa smiled. The Buddha remarked that Kasyapa alone of all his students had received his teaching for that day, and thereafter should be known as Mahakasyapa.

Chakora

Alectoris graeca, the Himalaya partrdige, lover of the moon, said to feed on moonbeams. A favored pet of Lakshmi. The eyes of the chakora are said to turn red when they look on poisoned food.

Bhairava

Bhairava (the “wrathful”) is one of the more terrifying aspects of Shiva. He is often depicted with frowning, angry eyes, sharp tiger's teeth, and flaming hair, stark naked except for garlands of skulls and a coiled snake about his neck. In his four hands he carries a noose, trident, drum, and skull. He is often shown accompanied by a dog. Bhairava is the embodiment of fear, and it is said that those who meet him must confront the source of their own fears.

In one version of the Bhairava myth, Brahma and Vishnu were disputing with each other for the status of supreme god and appealed to the testimony of the four Vedas, which unanimously proclaimed Shiva as the Ultimate Truth of the Universe.

Brahma was scornful of that answer, however, and his fifth head taunted Shiva: "I know who you are, Rudra, whom I created from my forehead. Take refuge with me and I will protect you, my son!"

Overflowing with anger, Shiva became Bhairava and severed Brahma’s head with the nail of his left thumb.

In another version, Brahma lusted after his mind-borne daughter and grew four heads in order that he might continually see her. Embarrassed by his attentions, his daughter ascended heavenwards. Brahma then manifested a fifth head and reached out to 'cohabit' with his daughter. Upon seeing this, Shiva became Bhairava and cut off the fifth head of Brahma with his sword.

The severed head immediately stuck to Bhairava's hand, where it remained in the form of the skull and served as his begging-bowl. Shiva as Bhairava then roamed the world as an ascetic, pursued by a female fury, to atone for the sin of brahminicide.

Skanda

Skanda is more commonly known as Kartikeya. He is a son of Shiva and was born without the assistance of a woman. The universe was being terrorized by the asura Taraka, and only a son of Shiva could destroy the demon. The other gods orchestrated Shiva’s marriage to Parvati, yet no child was born of the union.

Finally, Shiva handed over his semen to Agni, the only god capable of handling it, but even Agni was tortured by the semen’s heat, and was forced to hand it over to Ganga, who in turn deposited it in a lake in a forest of reeds, from whence Kartikeya was born. As he was born from the life-source that slipped (“skanna”) from Shiva, he is named “Skanda.”

The child Kartikeya was born in this forest and then suckled by the six Kartikas, or Pleiades. He developed six faces for this purpose, and has twelve arms, hence the name Kartikeya, by which he is commonly known and worshipped. He was made head of the army of gods, and, according to the Mahabharata, defeated Mahisa and Taraka, who through their tapas were threatening the gods.

One of the major Puranas, the Skanda Purana, is dedicated to him. In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna, explaining his omnipresence, says, "Of generals I am Skanda, the lord of war."

Durvasa

According to the Shiva Purana, Durvasa was an incarnation of Shiva. When Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva were sent by their wives to test the chastity of Anasuya, the wife of Atri, she turned them into three infants. Pleased with her, they granted her a boon, and she chose that the three gods should be born as her children. In due course, Brahma was born as Chandra, Vishnu was born as Dattatreya, and Shiva was born as Durvasa.

Durvasa became a great rishi in his own right, although he was infamous for his extremely short temper. When he became displeased, which was often, he would curse the person who caused him anger, and his curses were frequently potent. People dreaded his arrival.

In the Ramayana, Rama has an important meeting and asks his brother Lakshman to stand guard at the gate. In the William Buck version, Lakshman in his zeal declares that whoever intrudes on Rama’s private conference would be slain.

Unfortunately, Durvasa appears and demands admittance, and rather than disobey the rishi, Lakshman himself is forced to disturb Rama. True to his word, Lakshman surrenders his life and goes to heaven.

Urdhva Kukkuta

Urdhva: “upward,” kukkuta: “rooster.” The kukkuta can symbolize the eternity of time, and also adorned Kartikeya’s pennant.

Galava

Galava was a rishi and pupil of Vishwamitra. According to the Harivansa, Galava was Vishwamitra’s son, and that rishi, in a time of great distress, tied a cord round Galava’s waist and offered him for sale. From his having been bound with a cord (gala) he was called Galava.

Eka Pada Baka

Eka pada: “one foot,” baka: “crane,” a kind of heron or crane, Ardea Nivea. Also a name for Kubera, and also the name of an Asura said to have assumed the form of a crane and subsequently defeated by Krishna.

Koundinya

Koundinya was a rishi and the author of a commentary on the Pashupata Sutras. Also, the kingdom of Funan in Cambodia was founded in the first century A.D. by a Hindu named Koundinya. The Koundinya gotra exists in India today.

Incidentally, one of the five ascetics who became the first disciples of the Buddha Shakyamuni was named Ajnata Kaundinya. In the Lotus Sutra it is predicted that he will become a Buddha called Universal Brightness.

Astavakra

While still in his mother’s womb, Astavakra would listen to his father’s recitation of verses from the Rig Veda, and at one point, he told his father, “You’re reciting mere words. There’s no substance!” Astavakra’s father became angry, and he cursed his unborn son.

Thus, when Astavakra was born, he had eight distortions in his body — eight, astau, and crooked, vakra.

Despite his father's cruel curse, Astavakra remained a faithful son. When the boy was 12, his father lost a priestly debate and was banished to the watery realm of Varuna, lord of death.

Astavakra then undertook an epic journey — is there any other kind? — and traveled to King Janaka’s court to challenge the man who had bested his father. Janaka and his courtiers saw Astavakra’s deformed body and ridiculed him — but only until Astavakra opened his mouth, at which point the King and his court discovered Astavakra was a true sage.

Astavakra debated the priest who had bested his father and triumphed, winning his father's freedom. The people who once mocked him became his disciples, including King Janaka.

Pattabhi Jois also highly recommends reading the Astavakra Gita (or Atavakra Samhita). It’s an important treatise on Advaita Vedanta that consists of a dialogue between Astavakra and Janaka on Vedanta philosophy.

Purna Matsyendra

“Purna”: full or complete. Matsyendra, “Lord of the Fishes,” appears to have been an actual historical person. Born in Bengal around the 10th century c.e., he is venerated by Buddhists in Nepal as an incarnation of the bodhisattva of compassion, Avalokiteshvara. As with most Indian myths, there are many versions of the story of Matsyendra's metamorphosis into a realized adept.

In one popular version, the infant Matsyendra is thrown into the ocean because his birth has occurred under inauspicious planets. Swallowed by a giant fish, he overhears Shiva teaching the mysteries of yoga to Parvati in their secret lair at the bottom of the ocean. Matsyendra is spellbound. After spending 12 years in the fish's belly exploring yoga's esoteric practices, he emerged as an enlightened master.

Viranchya

A name of Brahma, with a suggested translation of “vira,” great, and anchy, “five,” “Great Five Elements,” which were generated by and are contained within Brahma. This may be folk etymology.

Viparita Danda

Viparita: “inverted,” danda: literally “staff” or “stick.” A staff given during investiture of the sacred thread. A staff or sceptre as a symbol of power and sovereignty.

In the Devanagari script, the danda is a punctuation character. The glyph consists of a single vertical stroke. In Hindi, the danda marks the end of a sentence, a function which it shares with the full stop (period) in many written languages based on the Latin, Cyrillic, or Greek alphabets.

Because of the shape of the danda glyph, the word danda is also a slang term for penis.

Eka Pada Danda

Eka pada: “one foot,” danda: “staff” or “stick.”

Viparita Salabha

Viparita: “inverted,” salabha: “grasshopper” or “moth.”

Ganda Bherunda

Ganda: “whole side of the face, including the temple,” bherunda: “terrible, formidable, awful;” in the Mahabharata, “a species of bird," the garuda pakshi or the eagle. A mythical two-headed bird that fed on elephants. The gandabherunda was used as an insignia by the Mysore royal family.

Hanuman

Durgaam kaj jagat ke jete

Sugam anugraha tumhre tete

Supta Trivrkrama

Supta: “prone” or “lain down to sleep (but not fallen asleep),” Trivrkrama: A name of Vishnu. A demon named Bali had conquered the four directions and driven Indra and the devas before him. Due to the peculiarities of his powers, he could only be defeated if and when his guru cursed him for disobedience. It was a situation that could only be contrived by Vishnu the preserver.

Thus Vishnu was born the youngest son to the rishi Kasyapa and his wife Aditi. The baby grew to be a dwarf and was named Vamana. Vamana visited Bali, who promised to give the short-statured Brahmin anything he could.

Vamana said that he wanted as much land as he could take in three steps. Bali agreed. His guru Suracharya, however, realized that Vamana could only be Vishnu, and begged Bali to retract his promise.

Bali replied that there could be no greater glory than if Vishnu himself were to seek alms from him. Suracharya became angry and cursed Bali.

At that moment, Vamana grew and grew in size — his first step encompassed the Earth and his second measured the heavens. He asked Bali where to take his third step. Bali bowed low and offered his head.

Digha

Digha: “long.”

Incidentally, the Digha Nikaya is the first division of the Sutta Pitaka in the Buddhist Pali Canon. The name literally means the “long” or “longer collection,” based on the fact that all of the suttas contained in are typically longer than their counterparts in the other sections of the Sutta Pitaka.

The Digha Nikaya includes a number of prominent and well-known teachings, as well as a significant amount of biographical information about the Buddha.

Trivikrama

A name of Vishnu. See above.

Nataraja

A name of Shiva as raja, “lord,” of the nata, “dance.” Nataraj, the dancing form of Lord Shiva, is a symbolic synthesis of the most important aspects of Hinduism, and the summary of its central tenets. This cosmic dance is called 'Anandatandava,' meaning the Dance of Bliss, and symbolizes the cosmic cycles of creation and destruction, as well as the daily rhythm of birth and death.

Raja Kapota

Raja: “king” or “lord.” Kapota: “a dove, pigeon.” In the Vedas often a bird of evil omen.

Eka Pada Raja Kapota

Eka pada: “One foot.” Raja: “king” or “lord.” Kapota: “dove, pigeon.”

Monday, October 30, 2006

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Oh Shit!

I know "Leaping Lanka" is sometimes an outlet for some real obscure shit (i.e. yoga, Roland Barthes, Axl Rose, PCP, constant and worrying references to muesli, comic books and crack-cocaine), but I'm so sparked on the news that Ivan Basso has left CSC.

Armstrizza and the boys at Disco better step up to the plate with a blank check or I will be sorely vexed. I mean really, you're gonna put Leipheimer on as your number-one stage racer?

I know road racing (on velocipedes, you heathens) rates just below organized professional booger-flicking in the sports consciousness of the American public, but trust me, Ivan drops nothing but hammers on the bike, and you should see the man climb! Ah, it'd bring a tear to your eye. In fact, I'm getting a tear in my eye right now thinking about stage 12 in the '04 Tour de France, a mountain stage in the Pyrenees, when Ivan, looking minty-fresh, edged past Lance for the stage win.

(Of course, Lance crushed Ivan several stages later by passing him — passing him! — while climbing up Alpe d'Huez during the individual time trial. But I digress.)

You may now return to your favored sports, Americans. These sports undoubtedly involve watching cavemen lining up and hitting each other in between commercials, watching grown men stand around on grass fields, scratching their balls and spitting tobacco as thousands of people in the stands fall asleep, or else watching rednecks speed around an oval for the upteenth time.

I know "Leaping Lanka" is sometimes an outlet for some real obscure shit (i.e. yoga, Roland Barthes, Axl Rose, PCP, constant and worrying references to muesli, comic books and crack-cocaine), but I'm so sparked on the news that Ivan Basso has left CSC.

Armstrizza and the boys at Disco better step up to the plate with a blank check or I will be sorely vexed. I mean really, you're gonna put Leipheimer on as your number-one stage racer?

I know road racing (on velocipedes, you heathens) rates just below organized professional booger-flicking in the sports consciousness of the American public, but trust me, Ivan drops nothing but hammers on the bike, and you should see the man climb! Ah, it'd bring a tear to your eye. In fact, I'm getting a tear in my eye right now thinking about stage 12 in the '04 Tour de France, a mountain stage in the Pyrenees, when Ivan, looking minty-fresh, edged past Lance for the stage win.

(Of course, Lance crushed Ivan several stages later by passing him — passing him! — while climbing up Alpe d'Huez during the individual time trial. But I digress.)

You may now return to your favored sports, Americans. These sports undoubtedly involve watching cavemen lining up and hitting each other in between commercials, watching grown men stand around on grass fields, scratching their balls and spitting tobacco as thousands of people in the stands fall asleep, or else watching rednecks speed around an oval for the upteenth time.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

White Elephant versus Termite Yoga Practice

White elephant or termite practice?

Manny Farber is one of the most important critics in movie history, a legend who penned classic pieces for The New Republic, The Nation, Art Forum, and Film Comment. He was an early champion of the American action film, as well as of Hollywood stylists like Howard Hawks, Don Siegel, Samuel Fuller, Preston Sturges, and even Chuck Jones. He’s most famous for the essays “Underground Films” and “White Elephant Art Vs. Termite Art.”

In the latter piece, Farber introduced and championed what he called “termite art,” a phrase he used to describe any unpretentious movie that “goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and, like as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity."

The tapeworm film is in contrast to “white elephant art,” or “masterpiece art,” which was “artificially laden with symbolism and significance.” The white elephant films of Michelangelo Antonioni, for example, “pin viewers to the wall and slug them with wet towels of artiness and significance.”

Dramatic, histrionic flourishes coupled with a rasping ujjayi breath might characterize a white elephant yoga practice, as each vinyasa and each asana is a neon sign blinking seriousness and “significance.” A key characteristic of white elephant art, according to Farber, is that it’s filled with “overripe technique.”

In contrast, the termite practice is laconic, workmanlike, efficient; a termite practice, as Farber defines termite art, “nails down one moment without glamorizing it, but forgets this accomplishment as soon as it has passed.” The termite practice is epitomized by an economy of expression.

To engage in a termite (or tapeworm-moss-fungus) practice, as the very name suggests, is to concern oneself with a burrowing into the many layers of the self, each layer as fine as onion skin, and not peeled so much as enveloped, chewed, swallowed, and digested, until one is left to confront the paradox of the self-devouring uroboros, the ancient Greek depiction of the snake or dragon eating its own tail.

You will not notice those termites at your studio as their economy renders them invisible. They will arrive, practice, and depart without drawing your attention. A termite’s practice is entirely separate from physical ideas of flexibility and strength; it is compact and internal.

Among the ways to cultivate the termite aspect of one’s practice, as Matthew Sweeney suggests in Ashtanga Yoga: As It Is, is to practice alone for an extended stretch of time. An unintended benefit of the solitary termite practice, as those around the world who practice alone know, is the deep and overwhelming sense of gratitude that arises, from deep in the core of the body, when one once again is fortunate enough to practice with a true teacher.

On a mundane level, a termite practice favors the rooting and grounding of the out-breath, while the white elephant practice favors an upward and expansive in-breath. The key difference is that both sides of the termite’s breath are directed internally, while the white elephant allows the breath to dissipate externally.

The stereotypical white elephant inhales and exhales with thunderous momentousness, and each movement up and down, forwards and backwards, is rigid with overwrought concern for perfection. It is over-burdened with floating fireworks and a concern for rubbery circus flexibility.

The white elephant is entirely dependent upon the strict division between the practitioner, the practice and, most critically, a sense of “spectators” who are “viewing” the practice. But it is this sense of performance that transmutes the white elephant. While practicing “on-stage” and acutely aware of the gaze of others, the white elephant self-consciously activates and engages each and every body part in a steady diffusion of consciousness.

So there is value in the white elephant practice, as true to its name, it inevitably lumbers inward: the relentless focus on the performance and perfection of each asana, and the interlocking vinyasa between, can only lead to the white elephant dissolving in the performance. From there, with a little grace, any sense of separation between performer, performance, and audience dissolves entirely. One thinks of Shiva’s aspect as Nataraj, whirling through his never-ending dance of destruction and creation. The dancer, the dance, the audience: all are one.

Who does not begin practice as a white elephant? Who does not enter a new studio or workshop as a white elephant? A key characteristic of the white elephant is its own self-consciousness, and who has never felt self-conscious? Whose practice does not flip-flop between white elephant and termite stages, sometimes even in the tiny space between the in- and out-breaths? The transition from white elephant to termite comes as one continues to practice: thoughts arise, one observes them, and one returns to the breath.

White elephant or termite practice?

Manny Farber is one of the most important critics in movie history, a legend who penned classic pieces for The New Republic, The Nation, Art Forum, and Film Comment. He was an early champion of the American action film, as well as of Hollywood stylists like Howard Hawks, Don Siegel, Samuel Fuller, Preston Sturges, and even Chuck Jones. He’s most famous for the essays “Underground Films” and “White Elephant Art Vs. Termite Art.”

In the latter piece, Farber introduced and championed what he called “termite art,” a phrase he used to describe any unpretentious movie that “goes always forward eating its own boundaries, and, like as not, leaves nothing in its path other than the signs of eager, industrious, unkempt activity."

The tapeworm film is in contrast to “white elephant art,” or “masterpiece art,” which was “artificially laden with symbolism and significance.” The white elephant films of Michelangelo Antonioni, for example, “pin viewers to the wall and slug them with wet towels of artiness and significance.”

Dramatic, histrionic flourishes coupled with a rasping ujjayi breath might characterize a white elephant yoga practice, as each vinyasa and each asana is a neon sign blinking seriousness and “significance.” A key characteristic of white elephant art, according to Farber, is that it’s filled with “overripe technique.”

In contrast, the termite practice is laconic, workmanlike, efficient; a termite practice, as Farber defines termite art, “nails down one moment without glamorizing it, but forgets this accomplishment as soon as it has passed.” The termite practice is epitomized by an economy of expression.

To engage in a termite (or tapeworm-moss-fungus) practice, as the very name suggests, is to concern oneself with a burrowing into the many layers of the self, each layer as fine as onion skin, and not peeled so much as enveloped, chewed, swallowed, and digested, until one is left to confront the paradox of the self-devouring uroboros, the ancient Greek depiction of the snake or dragon eating its own tail.

You will not notice those termites at your studio as their economy renders them invisible. They will arrive, practice, and depart without drawing your attention. A termite’s practice is entirely separate from physical ideas of flexibility and strength; it is compact and internal.

Among the ways to cultivate the termite aspect of one’s practice, as Matthew Sweeney suggests in Ashtanga Yoga: As It Is, is to practice alone for an extended stretch of time. An unintended benefit of the solitary termite practice, as those around the world who practice alone know, is the deep and overwhelming sense of gratitude that arises, from deep in the core of the body, when one once again is fortunate enough to practice with a true teacher.

On a mundane level, a termite practice favors the rooting and grounding of the out-breath, while the white elephant practice favors an upward and expansive in-breath. The key difference is that both sides of the termite’s breath are directed internally, while the white elephant allows the breath to dissipate externally.

The stereotypical white elephant inhales and exhales with thunderous momentousness, and each movement up and down, forwards and backwards, is rigid with overwrought concern for perfection. It is over-burdened with floating fireworks and a concern for rubbery circus flexibility.

The white elephant is entirely dependent upon the strict division between the practitioner, the practice and, most critically, a sense of “spectators” who are “viewing” the practice. But it is this sense of performance that transmutes the white elephant. While practicing “on-stage” and acutely aware of the gaze of others, the white elephant self-consciously activates and engages each and every body part in a steady diffusion of consciousness.

So there is value in the white elephant practice, as true to its name, it inevitably lumbers inward: the relentless focus on the performance and perfection of each asana, and the interlocking vinyasa between, can only lead to the white elephant dissolving in the performance. From there, with a little grace, any sense of separation between performer, performance, and audience dissolves entirely. One thinks of Shiva’s aspect as Nataraj, whirling through his never-ending dance of destruction and creation. The dancer, the dance, the audience: all are one.

Who does not begin practice as a white elephant? Who does not enter a new studio or workshop as a white elephant? A key characteristic of the white elephant is its own self-consciousness, and who has never felt self-conscious? Whose practice does not flip-flop between white elephant and termite stages, sometimes even in the tiny space between the in- and out-breaths? The transition from white elephant to termite comes as one continues to practice: thoughts arise, one observes them, and one returns to the breath.

Sunday, October 8, 2006

Espresso is that Crack

I've switched up my medication. I'm on this new Peruvian shit, Green Mountain Farms' light roast. All your liberal eco-conscious sensibilities will be assuaged, hippies, by the knowledge that yes, it's organic, shade-grown, and fair trade.

Some years ago, I used to read this guy's blog — I can't find it right now to link to it — that was concerned solely with coffee, chocolate and yoga. In fact, I think it was even called "Coffee, Chocolate, Yoga." Brilliant. And I mean really, what else is there?

To paraphrase Guruji, a.k.a. Big Boss, with one cup of coffee "even lazy man is coming full energy!"

Two cups? As I discovered last Sunday, two cups means a lazy man is a twitching, vibrating, and sweating mess of pinwheel supernova consciousness. To paraphrase Blake, I found out what was enough by discovering what was more than enough.

I've switched up my medication. I'm on this new Peruvian shit, Green Mountain Farms' light roast. All your liberal eco-conscious sensibilities will be assuaged, hippies, by the knowledge that yes, it's organic, shade-grown, and fair trade.

Some years ago, I used to read this guy's blog — I can't find it right now to link to it — that was concerned solely with coffee, chocolate and yoga. In fact, I think it was even called "Coffee, Chocolate, Yoga." Brilliant. And I mean really, what else is there?

To paraphrase Guruji, a.k.a. Big Boss, with one cup of coffee "even lazy man is coming full energy!"

Two cups? As I discovered last Sunday, two cups means a lazy man is a twitching, vibrating, and sweating mess of pinwheel supernova consciousness. To paraphrase Blake, I found out what was enough by discovering what was more than enough.

Wednesday, October 4, 2006

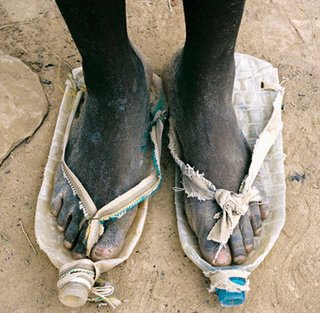

These Items of Footwear Have Been Crafted For Perambulation

Despite what I tell myself I want to be doing, my goddamn subconscious mind and my body meet in secret and conspire to tell me what I really want to be doing. They start with subtle messages, faint tugs and twinges of intuition, which, naturally, I ignore, thereby forcing the sneaky bastards to gradually increase the frequency and intensity of their missives, c.f. anxiety dreams, mood swings, back pain, and all-around physical tightness and constriction. When I've ignored all that, they unveil their piece de resistance, a motherfucking cold sore.

The point being, yesterday I walked off a job I didn't want and shouldn't have taken.

Despite what I tell myself I want to be doing, my goddamn subconscious mind and my body meet in secret and conspire to tell me what I really want to be doing. They start with subtle messages, faint tugs and twinges of intuition, which, naturally, I ignore, thereby forcing the sneaky bastards to gradually increase the frequency and intensity of their missives, c.f. anxiety dreams, mood swings, back pain, and all-around physical tightness and constriction. When I've ignored all that, they unveil their piece de resistance, a motherfucking cold sore.

The point being, yesterday I walked off a job I didn't want and shouldn't have taken.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)